What if we embrace that we're wrong a lot

Misalignments and errors shape our thinking. What if we learn to work with this?

Ants had infiltrated my home in Tucson. I woke up one morning to find a line of the super tiny ones streaming in near the kitchen faucet, searching for crumbs on the countertops. For various reasons, dealing with them required energy I didn’t have—it was like one more thing piled on during an already stressful time.

I think I spent a week hoping they would leave on their own and, as I recall, I even attempted to reason with them. I kept the counters extra clean too, whisking every plate, cup, and knife immediately into the dishwasher. Eventually, I cracked and bought a pack of liquid ant baits, cut one open at its plastic tip, and placed it under the kitchen sink.

I still had ants.

The next Saturday, I peeled into the parking lot of an extermination company that I’d never noticed before on Oracle Road. “I need help,” I said, launching into my story, which concluded with “and the liquid baits don’t work!”

“Where did you put them?” asked the sales associate, practically a runway model, notable because I did not know who to expect working at Do It Yourself Pest and Weed Control, but it wasn’t him.

“Under the sink,” I said.

He cocked his head and looked at me: “And where are your ants?”

We’re all susceptible

I’ve never forgotten this story because it’s such a gem of a cognitive distortion. Conflicting priorities clouded my ability to reason: I didn’t really want to kill the ants, and I didn’t want that sticky poison oozing onto my countertops either, yet I lacked the mental capacity to research other solutions. So, I hid my methods from myself.

In my defense, I believed the ants would find the bait under the sink the same way they could smell honey and butter on a crust of toast. But when my thought partner, the handsome exterminator, hinted that my problem and solution needed to intersect, the flaws in my plan became clear at once.

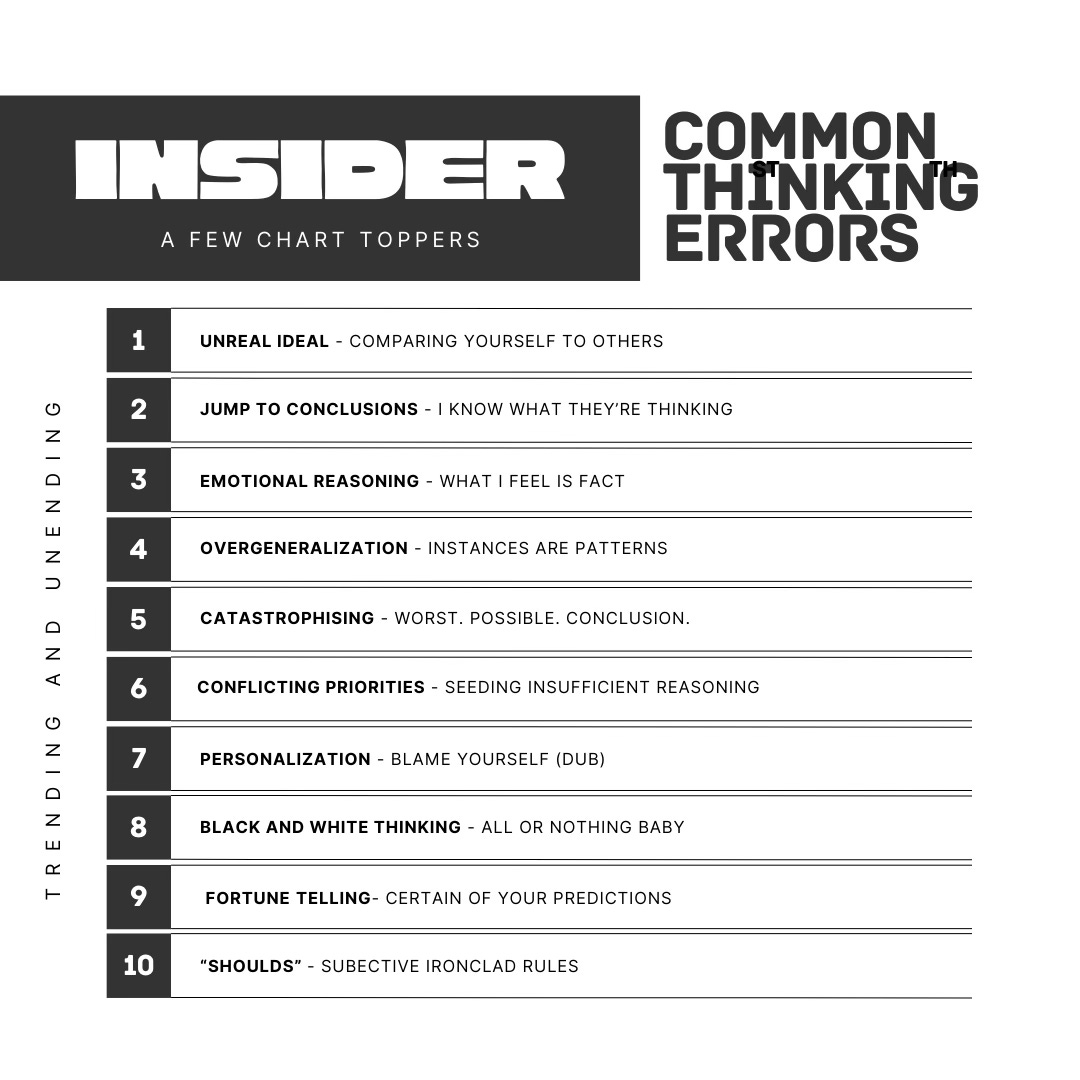

Conflicting priorities are an example of a common thinking error, but far from the only one. Here’s a few more greatest hits that we’re often susceptible to:

Rotting in the sun at the pool

I remembered my ant story the other day when I heard a podcast promotion for an online therapy company. In the ad, the hosts were bantering about how people will say “cooking is my therapy” or “playing tennis is my therapy.” Then they made the case on behalf of their sponsor that only therapy is therapy. I’m not a stickler about language like this—I want to believe that people understand rotting in the sun at the pool or drinking wine with girlfriends isn’t the same as doing the inner work, but the bit is funny because misalignments in our thinking are as basic as they are delusional.

Also true, my ant story was embedded in a more consequential reality. This all took place during the summer of 2016, in the midst of a US presidential election season not unlike today’s. In my personal life, I was leading a community arts organization undergoing tremendous cultural and institutional change, including embarking on a capital campaign. I’d bought a new house, but lacked the resources to do the renovations I’d hoped. And I had a broken heart to boot. I was steeped in problems I didn’t want and realities I struggled to accept. I had hope, fear, stress, disappointment—and tons of responsibility. So, in this context, what other, more consequential decisions might I have misaligned?

Why this matters

I’ve been considering why I take a stand for this type of educational content. I can write about anything, so why do I spend my time advocating for personal development? On the one hand, it’s how I’m wired—I’m optimistic, rational, and gravitate toward new ideas, progress, and people.

Coaching—and coach training, which I’ll get to in a second—also teach communication skills that I believe can help heal a world swimming in division and polarization. They help us recognize, and accept, that cognitive distortions are a part of the human design, not a design flaw. Then, they give us tools to work with this understanding.

Here’s an example. Along with several colleagues, I’m designing a coaching and leadership training curriculum for professionals in higher education, philanthropy, and the social sector. In this training, one of the foundational ideas is that “nobody gets to be right, and nobody gets to be wrong.” It’s not lip service, either. We mean it. As experienced coaches and trainers, we’ve seen firsthand the way this mindset can shift group dynamics in a room. Defensiveness and fear begin to recede. People’s bodies physically relax, their shoulders drop, and they begin to detach from their thoughts. They usher in more creativity, curiosity, and compassion as a result.

We can’t evolve past common thinking errors—at least, not entirely. With practice, we can grow more aware of some, turn down the volume on others, but we will always be susceptible because we’ll always be faced with challenges we didn’t anticipate, or problems we can’t solve alone. It isn’t humble to admit this; this isn’t about how we feel about being human. It’s about what we know to be true.

Deeply perceptive. JA