If you forgot you read a book, is it still part of you?

I reread some books from my childhood.

Many of the children’s books I loved growing up have migrated to my sister’s house over the years. She’s a wonderful curator and collector, and she read them to her kids, who may pass them along to their kids one day, which would be the fourth generation to hear some of them. A few books were special only to me I suppose, or not yet rehoused, so I took them home last week.

I’m struck by how simple and complex kids books are at once. If I skew my perspective to remember who I was back then, I can still recall my intrigue with each one, existential and practical. To be a kid is to have questions that you don’t know how to articulate, and that no one could answer even if you did. Actually that’s a pretty decent definition of a person at any age.

In a sense, to write about children’s books is to write about storytelling, but that beat is so well-covered that I don’t want to lean into it. We already know. We know they can save us, redeem us, and they can be used as strategies and weapons. We know they can be the marketing equivalent of boxes from Amazon, shipped efficiently, ordered with convenience, left on your doorstep. We know seats of power, churches and governments, divvy them by canon and apocrypha—some are true; the rest, negligible or worse, dangerous. I’m tired of hearing about stories this way, frankly. I’m tired of how they signal they’re on their way, then smirk with satisfaction after their performance. I’m tired of arguing about them, and the endless deciphering, everyone on the lookout for motives or advances. It’s exhausting. I’m exhausted.

But all of this sloughed off when I reread a handful of books from my childhood. They returned me to myself. Their agenda was so pure. Truly. Pure.

The Story of Ping by Marjorie Flack was first published in 1933. My copy is just a collection of pages now, gathered in a cover like a folder. Ping is a duck who lives on a boat on the Yangtze River with forty relatives, and every day, the ducks feed on the riverbank, and every evening, they march back onto the boat. If you’re the last in line to board, you get spanked. One day Ping was about to be last, so he hid for the night instead of accepting his punishment. This turns out to be a risky choice, but you’ll be happy to learn he eventually makes it home.

Stephannie and the Coyote, published in 1969, was written by Jack L. Crowder in English, and Agnes and Wayne Holm in Navajo. Stephannie (spelled Stefanii in Navajo) lives in a hogan with her parents. At age 7, she’s gone all day, herding sheep on a donkey and searching for the missing goat, assumed to be taken by a coyote. But the goat had actually given birth to two babies in a bush. Late in the evening, Stefanii finds them, carries the kids home, and reflects on others who may be lost.

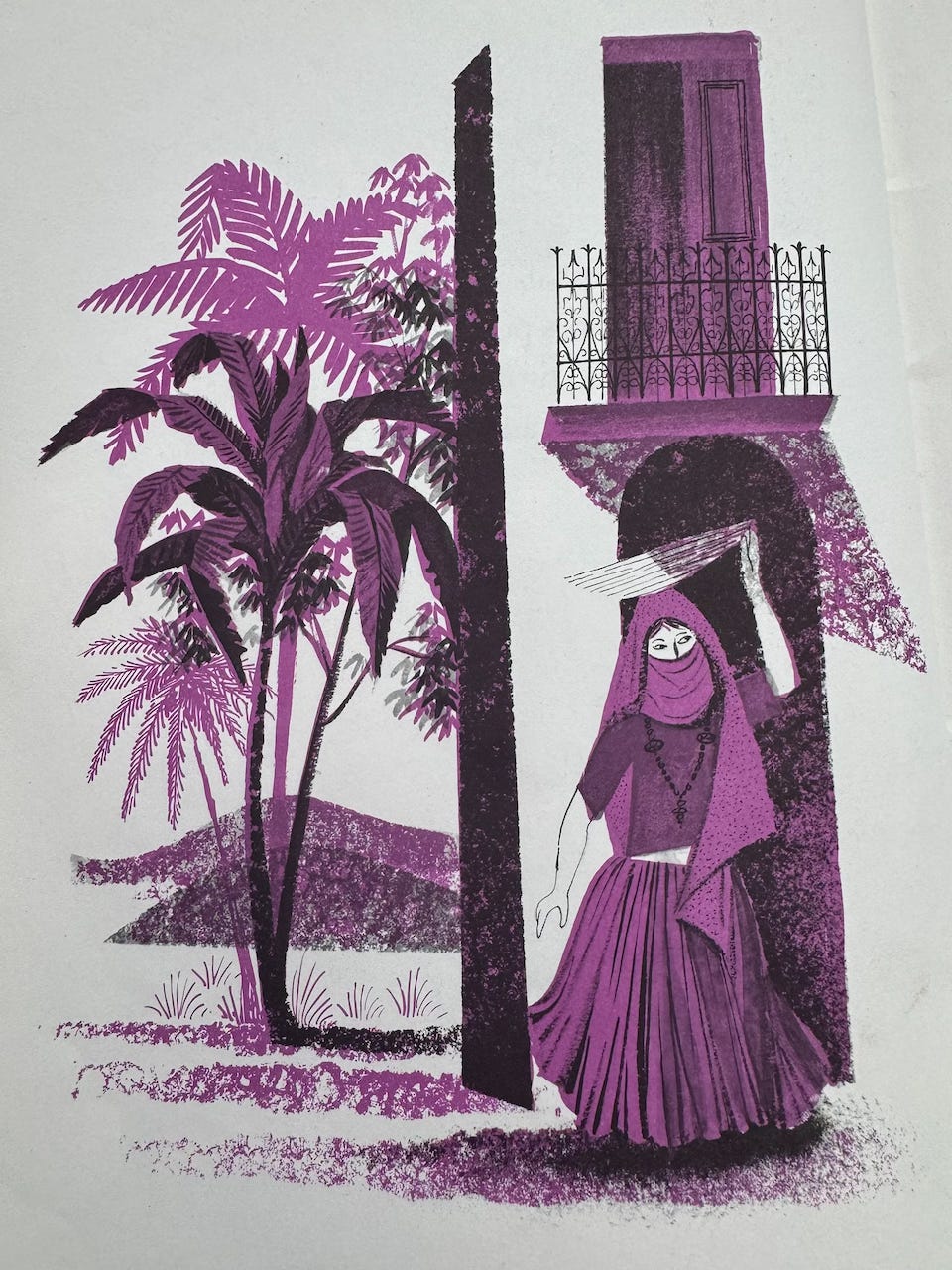

I am struck that my childhood was filled with stories of becoming lost and found, of people and families and cultures from all over the world, from the American South to New York City, Scandinavia to China. But if we forget these stories—if they were shelved in our memories as adults—are they still part of us, or more accurately, how are they a part of us? Hailstones and Halibut Bones by Mary O’Neill is a book of poems first published in 1961. Each one describes a color. I remember liking the one about red because it mentions lipstick, but “What is Purple?” was my favorite. It’s the most exotic and glamorous.

Time is purple Just before night When most people Turn on the light— But if you don’t it’s A beautiful sight. Asters are purple, There’s purple ink. Purple’s more popular Than you think . . . It’s sort of a great Grandmother to pink. There are purple shadows And purple veils, Some ladies purple Their fingernails.

The other week I wrote about how I’ve been spending time in the Guardian Angel Cathedral on the Strip, and how when I’m there I think about the layered, secular stories surrounding the church’s origin, including its location in the heart of soulless Las Vegas, and how it was funded by mobsters who were also philanthropists, and how the architect was a Black man who designed houses for the rich and famous in neighborhoods he was prohibited from residing himself. I suppose fundamentalists would label this sacrilegious, and a progressivist, an act of faith. When I’m there, sometimes I recall Christian parables, or stories that compose any faith, for that matter. How they’re moral dilemmas and ethical lessons without shoes. It’s just that we’ve decided to claim some and reject others; to believe only some are holy.

Recognizing truth in a broader set of stories is an edge that many people will never cross. I see how in the abstract it can feel unmoored, like we’re tossing out the rubric, and I don’t know what to say about that. Hysteria takes on a life of its own. Perhaps that’s when it’s essential to become like cultural anthropologists in our own lives, examining books as artifacts. I would not have told you that Stephannie and the Coyote or Hailstones and Halibut Bones were part of my personal canon because I’d forgotten about them. Now I want to claim them.

The truth of stories comes up in coaching contexts. I will say to clients quite often, “what is the story you’re telling yourself?” or “how do you know that story is true?” It’s not my job to determine what is true, but I point out when an arc sounds escalated, calcified and rigid, when I can hear in it limitations of the self, or others, as if to say notice what you are holding tightly, is that what you choose? Is it a stick of dynamite, a flashlight, or a fledgling bird.

“I tell my students, 'When you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else. This is not just a grab-bag candy game.’” ― Toni Morrison

Yes. You prove it here, that even if you forget about the story, it still made you. I love these stories you mentioned.

I have this one book called Lochinvar. It has incredible line drawings and is basically about a dog who belongs to a divorced woman who is partying a lot. LOL. (In retrospect, I don’t think it was a child’s book but I read everything.) Lochinvar chases off the ex when he shows up and ruins the party, and then the dog mother is mad, but in the end, she forgives Lochinvar and tells the dog that she loves him. So, unsurprisingly I was drawn to a book about unconditional love. 💕

Thanks for the post! Sitting here with the Lochinvar in my lap.

‘Stephanie and the Coyote’ was a favorite of mine as well…thank you for reminding me of it. I think a lot about children’s books my most treasured collection & how certain books gave me confidence to be an artist. Come to think of it they also inspired my style… I think I dress like Richard Scary characters! ;-)

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on your collection.