What's the story you're telling yourself?

(and the distinction between "feelings are not facts" and "emotion is data")

Letitia Boardman is one of my go-to confidants when I need informal spot coaching. She was the first person I partnered with as a student at the Co-Active Training Institute, and I still remember our initial, clumsy attempts at writing purpose statements together. We’d come from different backgrounds—hers in big tech and global enterprise; mine in philanthropy and nonprofits—and our experiences played nicely off each other.

One of Letitia’s superpowers is her ability to nudge me toward re-engaging with reason when my internal dialogue begins to veer off the road—when I’m feeling like I’m not enough, or too much, or that the world is collapsing and there’s nothing I can do about it, etc. In those moments, Letitia’s signature move is to ask, “what’s the story you’re telling yourself?”

With this intervention, I’m able to come back online in a more level-headed way. The query functions like a rudder, a blade redirecting my thought processes. If you’ve ever used a paddle to turn a canoe, you know the feeling of applying its force, creating high pressure on one side of the blade, low pressure on the other. The water’s resistance is strong at first—but it is possible to change course!

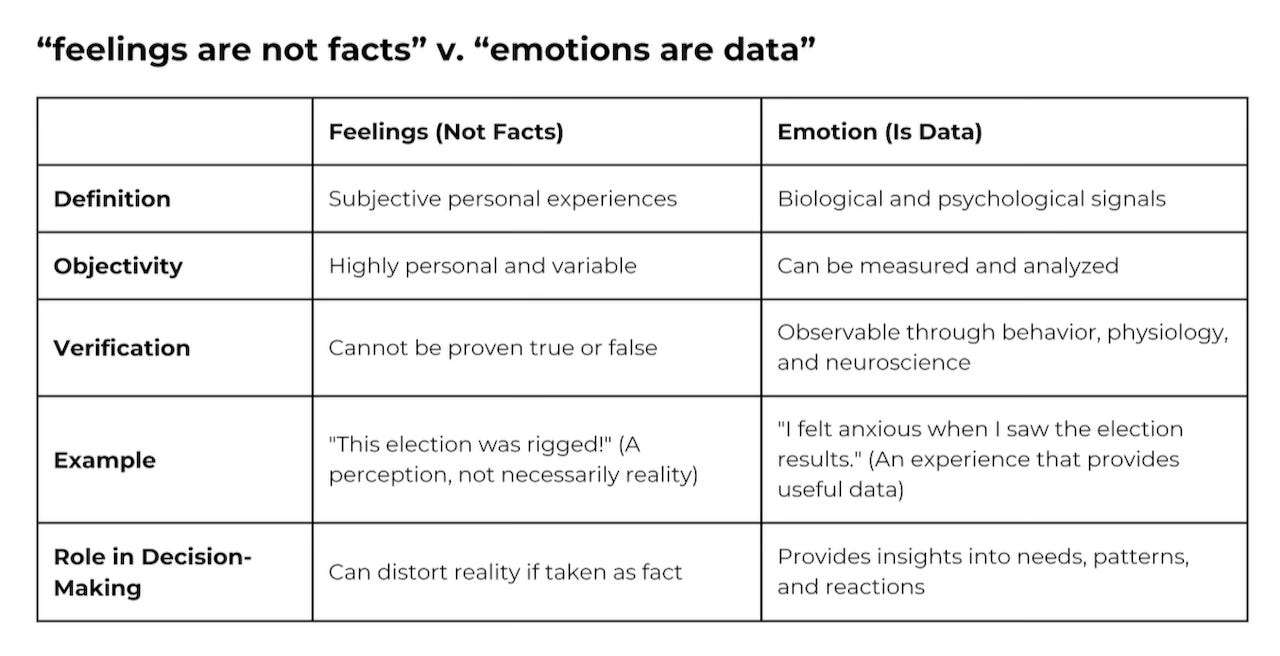

One way this question works is by distinguishing two, almost paradoxical ideas: “feelings are not facts” and “emotions are data.” Both are true at once, and they’re like a confluence of currents. Just because you feel something does not mean it is objectively true, and, emotions provide useful information that can help us make decisions, recognize patterns, and understand needs. Here’s a chart to explain it in more detail:

Here’s a few additional examples of feelings (not facts) and emotions (as data) drawn from the world of nonprofit and philanthropy. These aren’t specific to any one organization, but I’d be willing to bet you’ve heard, or expressed, some of them yourself—as have I. Notice your internal response to each as you read through this list: which ones heighten your anxiety? Which trigger empathy, understanding, or curiosity? Which feels most constructive?

“The board doesn’t help us fundraise!” v. “I’m frustrated that the board isn’t helping raise money—I wonder what’s stopping them?”

“Staff morale is at an all-time low.” v. “Some team members have expressed feeling frustrated and unheard—I’m concerned.”

“This organization doesn’t care about its employees!” v. “I’m disappointed my work isn’t more valued.”

“There’s no vision!” v. “I’m a bit lost—I don’t know where we’re going. What am I missing?”

“The board is totally disengaged.” v. “I’m worried that our board meetings lack participation—what’s preventing it?”

“We aren’t telling our story!” v. “I feel disconnected from our story. I wonder if that’s true for others?”

The first sentence in each pair are stories—they’re interpretations, expressions of feelings as facts. Even if they contain truth, they’re tough for others to engage with because they can’t be verified. (“Would a judge say so?”) On the other hand, when you report your emotion as data, the second sentence in each pair, you own that your feelings of anxiety, concern, frustration, etc., are your subjective experiences. It’s an acknowledgment that you may have a limited perspective, even if you believe that to be only ten percent true.

Expressing emotion as data requires introspection. It’s the request to name the emotional experience (“name it to tame it”) and that can be a challenge. You know how pop culture pokes fun at therapists for always asking “and how does that make you feel?” Well, the stereotype contains some truth: when a therapist or a coach asks this, they are, one, not making assumptions about your subjective experience; and two, encouraging you to gather data on yourself. They’re asking you to own your reality.

One more list. It’s additional reasons why you might consider expressing your emotion as data:

It improves critical thinking and decision-making. It helps separate bias from rational analysis, making you a more reliable narrator.

It keeps communication productive. When we express emotion as absolute truth, it shuts down dialogue and escalates conflict.

It reduces anxiety and emotional stress by swapping catastrophic thinking and panic for problem solving and ownership.

It enhances emotional intelligence, which helps us navigate personal and professional relationships more easily.

It shifts us from a victim mentality to a place of empowerment.

It deescalates conflict, transforming blame and defensiveness into curiosity and resolution.

It creates space for alternative perspectives.

It reduces manipulation and misinformation.

I’d be remiss not to point out that we’re prone to hyperbolic and catastrophic expression in part because we live in an age of nonstop self-promotion, advocacy, and personal branding. There’s lots of noise and chaos to cut through, and anger and anxiety are attention-grabbing and contagious … the hot take gets the most hearts, the squeaky wheel gets the grease, the crying baby gets the milk. This is a legit strategy, just not the best one when the goal is to lower the temperature, solve problems collaboratively, and forge authentic connections.

Also note that shifting your narrative approach takes time. You can’t read an article and get it. It’s more like learning to play the piano or water ski—it requires practice. Keep working at it, though. We need more emotional intelligence, rational actors, and engaged, thoughtful dialogue in our world—now more than ever.

Reach out and say hi if you want to talk about it further … would love to hear from you!

Really useful. I’m JT’s sister. You are very inspiring.