On a hot August afternoon in 2009, I was landscaping (quite literally … raking out construction ruts pressed into the soil) around an enormous house built into a meadow of my childhood stomping grounds in Flagstaff, Arizona. I was agitated. I wanted to restore the meadow, but I knew it would take years and still never be the same, and I felt pressure to deliver a landscape product that would complete this remarkable new house project. Stirring inside me was the awareness that the landscaping trade, per se, was not my true calling. Then, as if on queue, my phone rang. It was a different landscape client calling to ask if I would help her son’s 4th grade class start a garden.

That brief conversation would come to redirect and redefine the course of my life.

A few weeks later I found myself sitting on the floor with 10-year-olds, talking about the role and mindset of the gardener. I started with the basics of observation of weather, soil, light, and water. We asked ourselves questions like, what can we grow and why? What other living beings will be affected by our garden, for better or worse? Do we have permission? Where are we going to get the stuff we need? Who will care for it during the summer? Too many questions made us restless and so we mobilized to go meet the piece of land that would be our garden. Entering the courtyard, bound by two long wings of the school, one higher than the other in elevation, we passed through a shady thicket of ponderosa pine trees, and arrived at a sloped clearing at the West end. There were railroad tie remnants of garden beds awkwardly perched on the slope, their soil having washed away long ago, and engulfed in noxious weeds and pine needles. We lept into removing the weeds and picking up trash. On that first day, we forged a relationship with the land and made a commitment to care for it, and to be a team.

Week number two kicked off with a discussion about the word “legacy,” as developing this garden would be a long process, stretching far beyond these kids’ tenure at Puente de Hozho Elementary. The next step was to haul off the previous week’s enormous pile of seedy weeds, the rotting railroad ties and excess pine needles. This brought up the topic of taking responsibility for one’s trash, and awareness about its environmental impact. In an effort to practice principles of sustainability, we decided to henceforth export and import as little material as possible into or out of our garden.

As we worked and talked, the kids’ imaginations fired and one of the girls announced with conviction, “let’s pretend that this is our entire civilization.” She went on to describe how we would be self-sufficient and create our own beautiful world. That was the precise moment that hooked me into school gardening, and I now realize was the moment that conceived the nonprofit that would emerge a few years later, called Terra BIRDS.

Terra BIRDS’ vision is to bring nature to kids by way of the schoolyard. The late anthropology professor Miguel Vasquez, in describing the purpose behind reviving terrace gardens at the Hopi village of Bacavi, commented that “we are growing healthy kids.” The garden connects kids to their elders, and healthy eating habits. Foundational skills of team work, problem solving, patience and critical thinking are all required to build a garden, as are physical fitness and a strong work ethic. Opportunities for self-reliance and discovery abound in nature; but for kids who grow up with minimal daily access to nature, this experience may be denied. The subject of environmental degradation on a global scale can be overwhelming and depressing. But tangible solutions are readily available on the scale of a school garden.

Working with kids in the garden came to transform my worldview, as well. It blew open my definition of gardening, and set an anchor for optimism about the future. To this day, I still frequently make the point that the school garden is a microcosm of the world that kids will enter as their horizons expand.

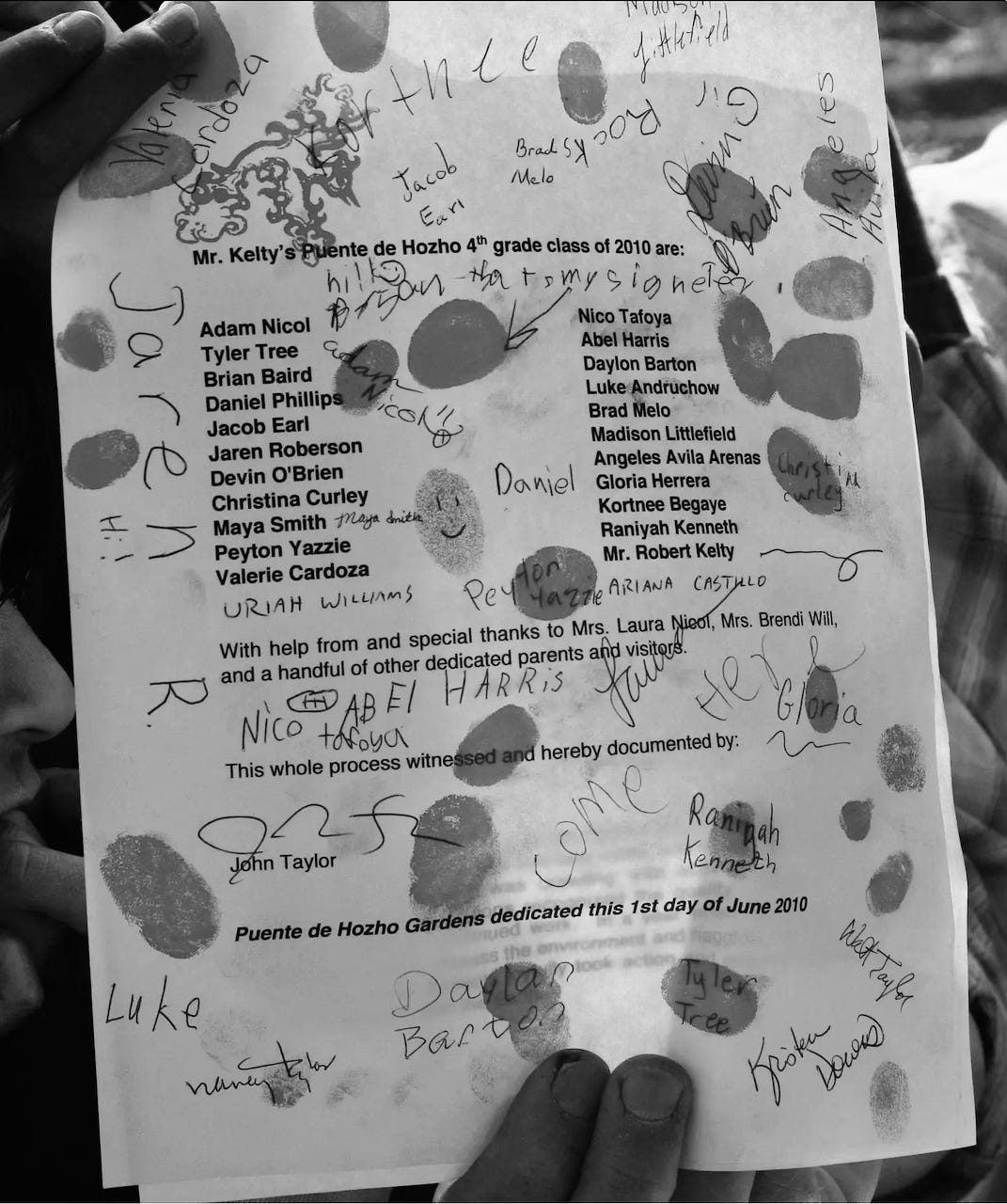

The following Spring, during their last session as 4th graders, the students and I signed a proclamation to carry our stewardship values forward into our lives, and buried it in the courtyard as a time capsule. Fifteen years later, those 4th graders are now well on their way into their young adult lives, and I hear from them and about them. I feel secure imagining them in positions of leadership, knowing the values we shared together in the garden. I trust them. Our work was about gardening, yes; but more importantly about building and stewarding a sustainable and equitable new version of civilization.

About the title: “Bridge to Beauty” is a reference to Puente de Hozho Elementary School. Puente is “bridge” in Spanish. Beauty, or the Beauty Way, is a translation of the Diné word hozho.